BL0UNTST0WN – Native Calhoun Countian Fuller Warren, Florida’s 30th governor who was found dead Sunday in his suite at a Miami motel, will he buried here Wednesday.

Warren is survived by two brothers, Joe Warren of Blountstown and Julian Warren of Jacksonville; one sister, Miss Alma Warren of Gainesville; two nieces, and four nephews.

Funeral services will be held at 3 p.m. Wednesday at the graveside in the Nettle Ridge Cemetery with the Rev. Samuel Lee of the First Baptist Church in Blountstown presiding. The eulogy will be delivered by U.S. Rep. Claude Pepper (D-Fla.)

Honorary pallbearers will include Florida Supreme Court Justice B.K. Roberts and Miami Beach financier Louis Wolfson.

Interment will follow in the Nettle Ridge Cemetery, with Martin Funeral Home of Blountstown in charge of arrangements.

The Dade County Medical Examiner’s Office reported Monday following an autopsy that Warren died of “hypertensive cardio vascular disease” — a heart attack. He had suffered for some time with a heart condition.

“He was apparently on his way to the kitchen to get some milk and he just plopped over,” said his brother Julian, of Jacksonville.

Warren was born Oct. 3,1905, and grew up in the northwest Florida pine woods cross road community of Blountstown, 45 miles west of Tallahassee. He was the third of seven children born to Charles R. and Grace F. Warren, who had migrated from Georgia.

He picked cotton at age eight for 75 cents a week plus room and board. As a teenager he performed varied odd jobs when not in school. He sold bibles in Alabama, served as a steward on a vessel at sea.

Warren entered the University of Florida at 18, waited tables at a boarding house for room and meals. He wrote for the school newspaper, joined the debating team and was elected sophomore class president.

The following year he won election to the house of representatives from Calhoun County at age 21 and took a leave from the University. He later obtained his law degree from Cumberland University and began practicing in Jacksonville.

He won election to the Jacksonville City Council and won a Duval County house seat in the 1938 legislature. At age 35, he made his first bid for the governorship, running a surprising third in the 11-candidate Democratic primary of 1940, the year Spessard L. Holland was elected.

World War II prevented him from running again in 1944.

Warren’s first political defeat came at age 13 when he made an unsuccessful bid to become a page boy in the house.

“I resolved then to master the art of politics,” he said. “I started immediately running for governor and I never stopped running until elected.”

As a boy, he found that his good looks, outgoing manner and deep voice were his biggest assets. He began as a young man speaking on any occasion that presented itself whether he had been invited or not. At his death, even he had lost count. The number of his public speeches totaled well over 6,000.

Warren underwent a hernia operation to win direct appointment into the Navy during World War II. He served 26 months as a gunnery officer aboard a troop ship, crossing the Atlantic 20 times. He also wrote the second of his three books, “[Speaking] of Speaking,” in which he counselled that it is better to concentrate on the sound of your speech than the content and to use 10 adjectives instead of one.

Warren was a prolific writer as well as speaker. His letters were lengthy essays. He wrote political columns for [newspapers] at various times and hundreds of letters to the editor. In his third book, published in 1948, was entitled “How to Win in Politics.”

It rose to embarrass him when he lost a 1956 bid to become governor again. He finished a low fourth in a six-man Democratic primary.

Warren launched his successful 1948 bid for governor by announcing his return from the war — city by city — in full page newspaper ads. He would borrow or rent an office in each city and enlist backers.

He also showed up at most anyone’s public occasion, often with a cohort who shouted: “Why! There’s ole Fuller Warren, folks. Come meet my friend Fuller.”

Warren topped a nine-man field in the first Democratic primary, then beat Dan McCarty in the runoff, which assured his election, by a slim 23,000 votes.

Warren became Florida’s 30th governor Jan. 4, 1949, with the greatest inaugural celebration the state had seen. More than 50,000 persons, including some of the 47 heads of state invited and a sprinkling of movie stars, poured into Tallahassee then rated a small town. Four inaugural balls capped the day, and Warren spoke at all of them.

Soon after taking office, he wooed and won Barbara Warren, a 23-year-old honey blonde from California who looked more like his pretty daughter. She was his third wife. The marriage ended in a 1959 divorce and Warren remained a bachelor thereafter.

“They were all fine women,” he said of his wives. “The fault was mine. I had no home life. I was always politicking.”

Warren, who served as Florida’s governor, from [1949]-1953, would have been 68 in 10 days, Oct. 3.

Looking back, historians are being much kinder to Fuller Warren than his legion of adversaries during his four-year term of the governorship.

He sat down in the “second hottest seat in the state — he said the first was the electric chair at Raiford State Prison — at a time when the state treasury was $5 million in debt and government was bankrupt in providing services and facilities stalled by World War II.

The state also was aching to shed its rural “Old South” cloak and go modern. Warren was the transition governor, and the storm of change broke over his head.

“All the chickens came home to roost during my administration,” he recalled.

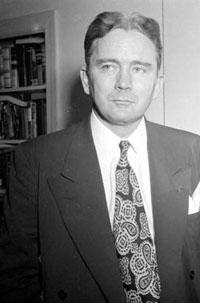

In his prime at 43, his hair already turning white. Warren attacked the problems with immense energy and vast verbiage. His only hobby was reading and it led to mastership of the English Language which rolled out over his outthrust chin with deep resonance.

Members of the press corps, with whom he feuded almost daily, probably used their dictionaries more than at any other time before or since. And they had to get Warren’s latest words spelled and punctuated correctly and without serious deletion or they would receive a prompt letter from the governor’s press secretary or his chief aids. This pair, doing the governor’s bidding, won the press sobriquet of “Fuller’s Comma Pickers.”

Although he had served two terms in the hou.se in younger days. Warren found few friends in the legislature. Many of the rural “Pork Chop” lawmakers, the ruling faction, considered him a self-serving traitor to his own rural upbringing. Articles of impeachment were introduced in the 1951 house but were rejected as being legally insufficient.

Despite this considerable opposition, Warren cajoled the legislature into ruling the cattle off Florida’s highways, a bill which had been defeated repeatedly for nearly 20 years despite the fearful loss of life and limb caused by the roaming cattle. Warren pointed to that act as his prime achievement.

But there were other noteworthy accomplishments. He pushed through the “taste test” citrus code which banned the shipment of green and poor quality fruit from the state. A “teetotaler but not intolerant,” Warren said orange juice was his favorite drink.

Years later, as an attorney opposing the addition of [sweeteners] to orange concentrate, Warren declared in one of the few uncluttered statements attributed to him: “I want our orange juice to be pure. It’s the only thing left that is pure.”

His administration built Florida’s first major expressway (at Jacksonville), St. Petersburg’s huge Skyway Bridge and began the planning of the Florida Turnpike; instituted a major [reforestation] project; earmarked auto license tag revenues for badly-needed school buildings, and established university scholarship funds from race track revenues.

Warren’s first legislature forced him to put a gun of political suicide to his head. It passed a huge appropriations bill and fell short by $70 million in providing the revenue to support it.

Warren convened a special session that September and presented it with 17 proposals to raise the needed money. The lawmakers rejected them and, instead, passed Florida’s first sales tax act. The governor was forced by the need to finance public schools into accepting it although he had campaigned on a promise to get the cows off the highways and to veto a sales tax bill.

But Warren managed to insist successfully that the lawmakers exempt from the three per cent sales levy all food, medicines, and low cost clothing. For many years, Floridans paying the tax with nearly every purchase referred to it as “Fuller’s tax.”

When Warren left office, Florida’s treasury had $50 million in reserve and a start on providing the facilities to handle a population which more than doubled in the next 20 years.

Despite his fights on the home front, Warren became Florida’s first “traveling governor,” ranging far and wide across the nation promoting the beauties of life in the sunshine state with a flood of melodic alliteration. He also established the first state-level agencies to promote both tourism and industrial expansion.

The thing that caused Warren’s ship of state to rock the most, however, was crime and the late Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver’s highly- publicized attack on it.

When Warren took office, an organized crime syndicate was running an illegal bookmaking business out of Miami Beach which netted a reported $26 million a year. Moonshiners flourished in the pine woods of north Florida and the bolita numbers racket took millions from the poor in the Tampa and central Florida areas.

Warren fired nine sheriffs and dozens of lesser officials during his term, but the Kefauver Committee made two trips to Florida. In 1951, with Maryland Sen. Herbert R. O’Connor succeeding Kefauver as chairman, the committee zeroed in on the governor. It disclosed that three millionaires, one race track owner with questionable friends, had personally kicked in at least $400,000 to finance Warren’s campaign for governor.

O’Connor drew national attention by issuing a subpoena ordering Warren to appear before the senate committee for questioning. The governor rejected the summons on historical constitutional grounds establishing state sovereignty. He al.so denied in his letter any collusion with criminal elements.

Warren could have served as a prototype for a novel about an Old South politician in the true sense of the phrase. It is a vanishing breed.

He was a widely-read country boy, lifelong Baptist and dedicated Democrat; war veteran, respected lawyer, Mason, Elk; an extroverted handsome, liable fellow with a deep booming voice.

Hillard F. Caldwell, who preceded Warren as governor (1944-48), said in a telephone interview from his Tallahassee home:

“Governor Warren was a better chief executive than he was given credit for. He accomplished many worthwhile objectives for the State. He was a delightful individual, a charming speaker and a good friend.”

State Comptroller Fred 0. Dickinson said, “He (Warren) had as much or more compassion than any man who ever served in public life in Florida. He loved people. With his loss passes an era and a truly colorful one.”

[Source: News-Herald, Panama City, September 25, 1973, Page 11]

[Burial: Nettle Ridge Cemetery, Blountstown]

Note: According to E. W. Carswell, writing for The Pensacola Journal on September 26, 1973, Fuller Warren attended the Thomas Industrial Institute in DeFuniak Springs. For more information, see Walton Past to Present.